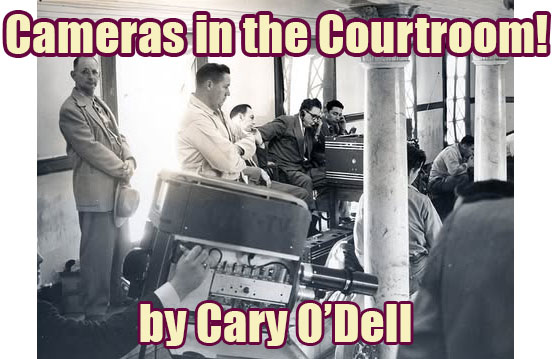

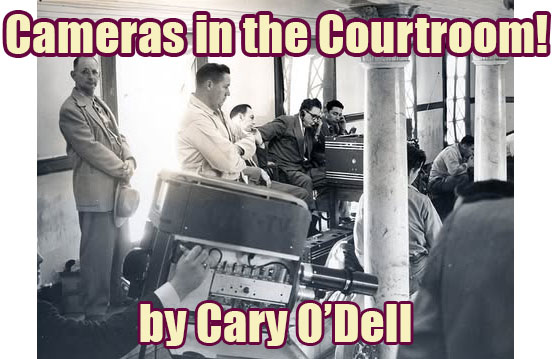

Smile! You’re on Trial! : When Cameras First Entered the Courtroom

Today, TV cameras in the courtroom are so common, so omni-present, it’s hard to remember a time when they were not the norm. Libraries and archives across the country regularly field requests from earnest researchers asking for film footage of just about every trial ever held only to be told, “No, they didn’t have cameras or cameras in the courtroom back then.” (A few rogue clips from the Lindberg trial and the Scopes trial, all over Youtube and often featured in documentaries, has only muddied the issue.) Today, TV cameras in the courtroom are so common, so omni-present, it’s hard to remember a time when they were not the norm. Libraries and archives across the country regularly field requests from earnest researchers asking for film footage of just about every trial ever held only to be told, “No, they didn’t have cameras or cameras in the courtroom back then.” (A few rogue clips from the Lindberg trial and the Scopes trial, all over Youtube and often featured in documentaries, has only muddied the issue.)

Interestingly, however, while cameras in the courts are new in terms of the American legal system, they are not that new in terms of American mass media.

TV viewers got their first glimpse, if not into the courts, then at least into official government proceedings, in the early 1950s, thanks to the televising of some of the hearings of the United States Senate Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce. These hearings, better known as the “Kefauver Hearings,” looked into the role that organized crime played throughout the USA and they presented to the viewing audience an absorbing array of underworld witnesses, a true rogue’s gallery of mobsters, molls and thugs. Among them: Mickey Cohen, Tony Acardo, Frank Costello and Virginia Hill.

Since these were Congressional hearings, held by the US government, it was no doubt deemed that they were (or might be) of interest to the American people. Hence, the cameras ran. And, to the surprise of many, viewers found the coverage quite riveting. In March of 1951 alone, it was estimated that over 30 million Americans tuned in to watch a least some of the testimony.

But government hearings are different than your local courts where, presumedly, what occurs is only concern of the judge, jury and defendant.

Still, it didn’t take long after the Senate hearings for TV cameras to make it into at least a couple of much smaller courtrooms. The very first was in December 1955, in Waco, TX.

In 1955, Harry L. Washburn was on trial for the murder of his ex-mother-in-law, Helen Harris Weaver.

Earlier that year, on January 19, 1955, Helen Weaver, described as a “rancher,” socialite and the wife of a respected local architect, died when she got into her car in the driveway in front of her well-appointed home in San Angelo, Texas. Soon after she climbed in, the vehicle exploded, mangling the car and killing Mrs. Weaver.

After Mrs. Weaver’s death, it took only ten days for Texas authorities to make an arrest in her murder. Harry Washburn, listed in the press at the time as a “38 year-old contractor,” was arrested in an early morning raid carried out on the morning of January 29th. Police acted on tips from two former associates of Washburn’s who filled them in on the fraught relationship he had with his ex-wife’s family. Washburn had never really gotten along with his in-laws and their interactions became even worse when various businesses they had set Washburn up in all failed under his watch. Later, still in need of money, he began to extort them, demanding money from them to see their grandchildren. Later, still demanding money, he simply threatened them directly.

Not long after Washburn’s arrest it was disclosed that when the bomb went off, Washburn was actually miles out of town, riding in a car with a man named Andrew Nelson. According to Nelson, when the announcement of the murder came over the radio, Washburn cried out, “My god, that’s the wrong one!” Apparently, Washburn had intended to kill his ex-father-in-law, not his ex-mother-in-law. Apparently, Washburn hoped that after killing his ex-father-in-law, he’d be able to extort the remaining family for money in exchange for his “protection.”

Though Nelson, a man who had had frequent run-ins with the law, may not have been the best witness, his testimony along with the info from a couple of other tipsters was enough for the cops.

Washburn’s Texas trial was set to begin in December of 1955 but, as is often the norm, there were various pre-trial maneuverings. The first was the defense’s call for a change of venue. They argued that the amount of pre-trial publicity surrounding the case tainted the local jury pool. They asked for and got a change of location: from San Angelo to Waco, a town about three hours east.

This sort of motion was not that unusual but the next one was. Once moved to Waco, local TV station manager Buddy Bostick of Waco station KWTX-TV argued that the citizens of the area had a right to view the proceedings and asked for permission to broadcast the trial, live, gavel to gavel. Though the case was, technically, the People of the State of Texas v. Washburn, it is questionable if Washburn could be categorized as an enduring threat to the public. KWTX’s interest in broadcasting the trial seemed to be more about capitalizing on the salaciousness of the trial than keeping the citizenry informed.

Still, to the surprise of many, after consulting with all the principals involved in the trial, the presiding judge in the case, Judge Drummond Bartlett, agreed. Hence, the trial began, and the camera rolled, beginning on December 6, 1955.

Newspapers throughout the area sought out opinions about his development. Surprising, the majority of local lawyers saw little harm in the addition of a camera. Tom Moore, Jr., a District Attorney from Waco said at the time, “I like it, because people will know how these things are handled. Most of our general public doesn’t know how these things are run. It will lead to better jurors.”

But for all the legal approval about the cameras, there was dissent. Other attorneys not directly associated with this trial, decried the addition of this technological invasion. They maintained that the mere presence of a camera in the court would corrupt the process, turning a proper legal proceeding into just so much tawdry theatre.

Though Judge Bartlett allowed the camera into the courtroom, he nevertheless imposed some restrictions. Most importantly, only one camera would be allowed in the room and it had to be as inconspicuous as possible. Thus, KWTX set their camera up in the balcony and out of the view of the jury.

In order to broadcast however the courtroom had to change a little. First, the station had to change out all the lighting in the room: just before the trial started, the 50-watt lightbulbs in the courtroom were switched out and replaced to 100-watt bulbs. Additionally, microphones—at the judge’s desk, at the witness stand and at the prosecutor’s table—had to be installed and hidden as best they could.

Once the trial began, the coverage was a hit. The case possessed enough sensational elements to incite a wide swath of public interest. It had, after all, wealthy, old-monied Texans, some very low-life hoodlums, and all sorts of intrigue including new allegations that involved Washburn possibly attempting to hire a hitman for Mr. Weaver only a few months before the fatal car bombing. Public interest in the trial reached a fever pitch when Adela Henniger, a witness for the prosecution, was called to the stand. Ms. Heninger worked as a local lady wrestler and went by the name “Nature Girl.”

It was rumored that the streets of the local towns were barren whenever the case was on. And, it airing in December, caused local merchants to complain that all their Christmas-related sales were being affected as shoppers stayed out of the stores and at home to watch the trial!

Thankfully, for them, the trial was rather short, lasting only four days, from December 6th to December 9th. Washburn was found guilty and was sentenced to life in prison. (Interestingly, his conviction was overturned a year later and he was tried again in Houston in 1957. Once again, he would found guilty and was subsequently sentenced to 99 years in prison.) Washburn died in prison in 1979.

For KWTX, however, though they might have garnered a lot of attention by broadcasting the trial live, they also lost a lot of money on their coverage. To air it, the station had to jettison all their commercials that would have aired during that time. Hence, for every second that the trial aired, they lost money. By the end of it, the station had lost around $10,000. That deficit (well over $100K in 2025 dollars) might explain why neither KWTX nor other stations in the area jumped on the cameras-in-the courtroom trend.

However, in regard the idea of cameras in the courtroom, the ice had been broken. In April 1956, not long after the Texas trial, up in Colorado, the trial of Jack Gilbert Graham, who was accused of blowing up Flight 629 out of Denver—a disaster that took 44 lives—saw his trial recorded by cameras but, notably, not aired live. Additionally, in this proceeding, the judge was equipped with a special switch that allowed him to deactivate the camera at any point during the trial should he deem it necessary. Finally, for this trial, any participant or witness who did not want to be photographed could opt out of being. One who did was the defendant himself, Jack Graham.

Graham, who put dynamite on the plane to kill his own mother, was found guilty in 1956 and put to death in the gas chamber in 1957.

Today, of course, the presence of cameras in the courtroom seem more common than not. They helped make the O.J. Simpson trial the spectacle it was and courtroom footage today serves as the backbone not only for CourtTV but also for a variety of other shows from “48 Hours” to A&E’s “CourtCam” series to every single “true crime” program currently on the air (and there’s a lot of them!).

Ironically, though, now it’s a verity, the debate about the actual need for their presence in the courtrooms still rages and, remarkably, it’s the same old pro and con arguments: it’s for the “public good” and education versus it taints the proceedings…

But until those get settled, I guess, just enjoy the show!

|

|