|

by L. Wayne Hicks

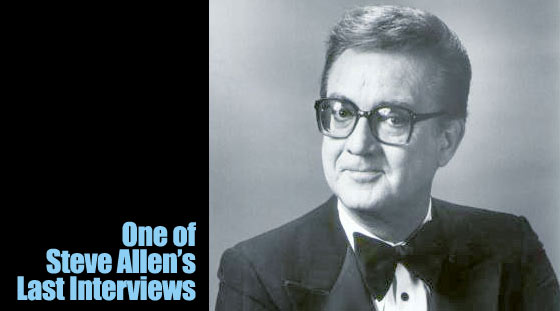

Steve Allen left an impressive string of credits when he died at age

78 on Oct. 20, 2000. Notably, during the 1950s he created the format for

the television talk show that’s still in use today. The passage

of time keeps younger audiences from knowing exactly the debt David Letterman,

Johnny Carson, Jay Leno and others owed Allen. Carson’s Carnac the

Magnificent, for example, in which he would think of a funny question

to go with an answer, was a direct lift from Allen’s Answer Man.

Born in New York to vaudeville parents and reared in Chicago, Allen first

began to make waves while working as a disc jockey in Los Angeles. Allen’s

quick wit served him well when he began to banter with the audience. Finding

humor in the everyday, in the average person, became a staple of Allen’s

comedy.

Allen

moved to New York to create a late-night television talk show for the

NBC affiliate there, and the network itself began airing it as “The

Tonight Show” in September 1954. Two years later, Allen added to

his responsibilities with a Sunday night variety program meant to compete

against “The Ed Sullivan Show.” He left “Tonight”

in 1957 to devote his energies to the weekly show, which was moved to

Monday after failing to make a dent against Sullivan. Allen

moved to New York to create a late-night television talk show for the

NBC affiliate there, and the network itself began airing it as “The

Tonight Show” in September 1954. Two years later, Allen added to

his responsibilities with a Sunday night variety program meant to compete

against “The Ed Sullivan Show.” He left “Tonight”

in 1957 to devote his energies to the weekly show, which was moved to

Monday after failing to make a dent against Sullivan.

Although Allen was a powerhouse in the television industry during the

1950s and 1960s, serving as host of a variety of programs, he turned his

attention in later years to writing: songs, novels, nonfiction books.

During an interview conducted with L. Wayne Hicks in 2000, Allen reflected

on his accomplishments and how “The Tonight Show” got started.

Q: How do you keep your sense of humor?

A: I have no idea. It's like saying to me how do I keep

the color of my eyes consistent? It’s just part of what I am. Literally

everyday amusing thoughts occur to me, or amusing interpretations of events

that I experience of witness, but there's nothing I do. I don't take Vitamin

C to make me funnier or read funny books or whatever.

It's very much like asking a composer how in the world do you keep maintaining

the ability to create all of those lovely melodies? He doesn't understand.

He may have done his homework or he may have, as in my case, be something

of a freak. I can't read music. I don't know any musical terms, but I've

now written about 8,500 songs and if I live a few more years I'll probably

reach the 10,000-song level and there is no difficulty in that activity

for me. I once wrote 400 songs in one day as a public demonstration at

a musical convention in Michigan. So I don't really feel I deserve any

great credit for that. If songwriting were terribly difficult for me,

if it were torture, if I had to sweat over every note, then I suppose

I'd let people throw me an honorary dinner or two. It has nothing to do

with modesty. I literally don't feel that anybody else should be impressed.

I hope they like the songs and millions apparently do, but it's as if

I was just standing around and some notes came out of my head and they

were put on paper by somebody they made sense.

That's about as close as I can come to an explanation, which is of course

no explanation at all.

Q: At this point, how would you like to be remembered?

As a composer, as a comedian, as an author, as a father, a husband?

A: Well, I am all of those things. I realize I present

a little more troublesome problem than the average person, most of the

human race; probably 99 percent of the people in the human population

who work do one thing. They may also be included in other things. They

may be Republicans, they may be conservative, they may be fathers, they

may be citizens of Detroit. You can have a pretty long list of that sort

made out. But as regards their work, they generally do one thing. So those

of us who are versatile, which I attribute largely to genetic factors,

or perhaps solely to genetic factors, are in the simple biological scientific

sense of the word freaks, and freaks are very difficult to explain.

Q: You invented the late night talk show, everyone now

knows if you're going to do a talk show you have to have the band leader,

the desk, the chair and the monologue. You were the first. How did you

decide what to do, and how much experimenting did you have to do?

A: Well, the experimenting had already been done. I developed

the show, as you have apparently perceived, by more of a workshop, experimental

process than by creating the show the way one might create “Who

Would Like to be a Millionaire” or whatever that thing is called.

There are shows with very rigid and very original formats, formats never

before even contemplated much less produced. But creating “The Tonight

Show” specifically or the talk show generically was not such a creative

exercise. The experimenting in fact was done on radio since I worked in

radio before there was television. It existed in the technical scientific

sense but it wasn't available to performers or the public until around

1948 or so.

I had been doing conventional comedy, in other words writing comedy scripts

the same way Bob Hope and Burns and Allen and all the comedians and non-comic

performers in radio. Somebody would write a script. Bob Hope would hold

the script in his hand, all 37 pages of it and fold over the pages one

by one and just read the words and all the other members of his cast would

gather around the same microphone and read their words off the paper.

There's nothing wrong with that. It gave us some of the greatest radio

in cultural history.

While I had started in that way I didn't continue in that way and therefore

inevitably created “The Tonight Show.” After two years of

doing a straight comedy show called “Smile Time” on the Mutual

Radio Network, that program was simply canceled as all shows are all eventually

and I was on the street again looking for work. The only job that was

offered to me was to come over to a CBS station, station KNX in Los Angeles.

At first I was very gratified to be a working man again, but I was very

displeased when I heard what they wanted me to do, which was simply to

introduce recordings. What was later called disc jockey work.

Q:

Not a very creative job. Q:

Not a very creative job.

A: No. All you are if you're a disc jockey is a radio

announcer, which is a perfectly legitimate way to make a living.

Q: But not what you wanted to do.

A: It's not what I wanted to do, no. There are thousands

of radio announcers. They're generally nice law abiding gentlemen who

have pleasant voices and that's the only requirement. They could be serial

murderers as far as their personal life is concerned, but if they have

a nice voice they can make a good living selling that voice, commercials

or time segments or whatever. Nevertheless, I had to take that job but

I very quickly began to break out the boundaries of the show.

When I first started it, I don't remember how many records were played

in an hour, let's say 10 of them, and I cut it down little by little.

Nine, eight, seven, so forth. And finally it came to the attention of

my employers that I wasn't doing what they had hired me to do. I had begun

to play the piano live and to sing a bit and to say funny things and to

read letters and open cakes people had made and sent in to me, that sort

of thing. I got a call one day. In fact the fellow dropped into my office.

A man named Hal Hudson who'd hired me in the first place. A very nice

fellow at CBS. His point was that he would appreciate if I would get back

to do what they had hired me to do, introduce recordings.

I said, “Well, I have a counterargument. Give me a moment and hear

it.” I said, “You have 12 other stations on the air at the

same time and on every one of those stations“ — those were

the days, I should explain, when radio stations all over tried to be all

things to all men; there were just a few classical music stations, but

other than that all the stations tried to do everything. And I said, “I

am giving the listeners something different and judging by the mail they

like it.”

He said, “Well, I didn't come here to debate the thing with you.

If you want to talk a bit that's no problem, but stick to the record.”

And then a day or two later he sent me the same point in a memo. Well,

I did a thing which was either stupid or brilliant as may be interpreted.

I read his letter in its entirety, his memo, and the reaction was glorious.

We got hundreds of letters. I had never gotten to that point more than

five or six letters a day. I got literally hundreds of letters al of which

were on my side of the argument and some of which repeated the very points

I had made to him. Their point generally was “There are a bunch

of other guys who were playing records a lot longer than you have. If

all we want to hear is music, to hell with you. But we're interested in

that you're doing something else.”

Q: They didn't want just music anymore.

A: Well, it wasn't that they suddenly decided they didn't

like music. They could get music 24 hours a day, anytime, or play their

own or what have you. But whatever they discovered in me they were preferring

to the typical disc jockey work. A few days later I had all these letters

gathered in a grocery box and I walked into Hall's office. I said, “I

know you're busy, but I think you'll be interested in the content of these

letters.” He said, “I heard what you did reading my memo.

Are these the answers”? I said, “Yeah.” He said, “All

right. Leave them there. I'll check them out.”

The story had a happy ending. Sometimes from that impertinence you can

get fired. But In this case he came back a couple of days later. He said,

“All right. I didn't read all the letters, but I read enough to

convince me that those particular listeners want that, so go ahead and

do the show anyway you want.”

That was a great breakthrough. Very shortly, I was down to about one record

for the 30 minutes. At that point it was a 30-minute show. But then came

another marvelous development in terms of its eventual effects. Because

the show was suddenly getting to be the most listened to show in the time

slot, the station stretched it out from 30 to 60 minutes. Unfortunately

there was no increase in pay to me. To that point I had been spending

maybe two hours in the afternoon at the typewriter, writing a few little

jokes or sort of Andy Rooney-type humor, whatever I wanted to talk about.

But I thought I'll be damned if I'm going to spend four hours here with

no more money. At that point I had the idea of interviewing people, which

had been going on for years. The easiest people to book as guests were

people who had made recordings and wanted to promote them. So I had a

lot of great singers and bandleaders and musicians as guests. Then another

development had occurred along about that time. People began to write

in for tickets to the show. In those days people liked to go see the Bob

Hope Show or whatever was available, the Jack Benny show, because they

could hear other people laughing. Also tickets were free so it was a good

deal for everybody.

Q: But you didn't have an audience.

A: Well, those shows did have audiences of course. They

had big studio audiences but to that point I did not. In fact I was still

in the studio that was about as large as the office I'm in here at the

moment, the size of an average office room. As people began to write in,

I would say on the air and sometimes write to them we don't have any tickets.

It was not perceived as an audience thing. But if you want to come down,

we have six or seven chairs. Pretty soon I had eight, 10, 12, 14 people

in the room and if anything funny was said they would laugh their heads

off. Now audio factors being what they are, if you hear 14 people laughing

for some odd reason, they make a lot of noise, that many people laughing

simultaneously. So the impression soon became common on the part of our

listeners — God, these are long answers — people thought it

was just like going to the Jack Benny Show or the Burns & Allen show.

Pretty soon the station began to print tickets and they gave us a larger

studio. I did two shows. One taped for the following Monday so I got a

night off. The studio held about 1,000 people. It was where the big CBS

comedy shows and other dramatic shows came from. People would stand in

line for about two hours to get in. I hated that part of it, but it was

their decision.

Q: Did that change your performance?

A: Oh, yes. If made it much more effective. If you say

something funny, a funny comment is followed by the laughter of 500 people.

That's an entirely different experience for the listeners, for the observer,

than just hearing a witty man saying things quietly to himself,

or his engineer, his guest at the moment. It sounds like a big party and

it was. So the show quickly became the big time nighttime show in Las

Angeles. In fact because the station was a 15,000-watter, we got fan mail

from all over the country.

I forgot one very important moment. One night a guest who was scheduled

to be there — Doris Day — didn't show up. It wasn't her fault.

So suddenly I was faced with 30 minutes of live air time. I'd already

played a couple of piano things, I couldn't go back to that. I read two

or three funny letters. I opened a sweater somebody had knitted for me.

I had nothing to do. It was kind of a scary element to that experience.

The only thing I could think of to do was to lift up the big old standup

mike and lug it, heavy as it was, around the studio audience up and down

the aisle. A remarkable thing happened. I got bigger screams, bigger laughs,

from that than from anything that I had ever done before.

So I realized at the end of that night that I had stumbled into a great

discovery and to stumble into something is not by any means the same as

creating it. Nor am I the first person ever to have gone into an audience

but no other comedian had ever done so. There were square people and announcers

who had gone into the audience, asking who was the oldest lady in the

audience or whatever.

Q: You found humor in the audience, just talking to regular

people.

A: Yes. Just talking to plain folks. Sometimes the factor

was they were so nervous they would say goofy things. One example comes

to mind. I had interviewed the first four or five people in the audience.

I let the conversation run to whatever length seemed natural and then

I would move on to somebody else. I suddenly turned to the other side

of the aisle.

Now I very often had asked people where are you from. Sometimes they'll

say, “I'm from Butte, Montana” and you talk about cowboys

or buttes or Montana or something. It gives you something to talk about

if you know where they're from. So I turned to the next guy on the other

side of the aisle. I said, “And what is your name, sir?” And

he said “Boston, Massachusetts,” expecting that I was going

to ask him where he was from. That's not a formal joke, but it obviously

got screams of laughter. So many of the laughs that came in those segments

of the shows were just sort of falling off the train.

The situation was funny in a way that it wouldn't be if I walked up to

a stranger in the park who had no idea who I was. He'd probably tell me

to get lost if I started asking him personal questions about his hometown

and where he met his wife and stuff. So anyway that was the first big

experimental workshop out of what would eventually became the formula

developed. At this point the glamour of radio was slightly beginning to

disappear and of course it was immediately replaced by that of television.

So CBS brought me to New York where I worked for the following decade,

the 1950s, although I was with CBS for only a total of seven years and

then I joined NBC and went on to do a show with a little larger budget.

That's sort of how the pieces of the show were put together. They were

all constructed for my personal convenience.

Q:

Did the network originally want to carry“The Tonight Show”? Q:

Did the network originally want to carry“The Tonight Show”?

A: There was interest on the part of Pat Weaver, Sylvester

Weaver, who was the chief programmer for NBC, very early. Since I wasn't

working for him at that time — I was employed by CBS — he

naturally had no freedom to call me and offer me the job, if indeed he

knew who I was since I was working in Hollywood. They gave some

thought to various comics. They probably ruled out immediately about 90

comedians in the business because for obvious reasons they wouldn't be

right for that kind of study. But his representatives found another young

fellow. His name was Don Hornsby. He had the nickname Creesh; I have no

idea why. I had heard about him. I went one night to see him. He was funny.

He worked a little bit like me. Neither of us was influenced by the other

because I was on the radio and he worked in clubs and we had our own separate

styles. But what we had in common was we both worked from the piano bench

part time. He would work at a piano with loose-leaf books of old jokes

and old parodies and old funny songs, so in that way we weren't alike.

Anyway, he was NBC’s choice.

They had nothing. The word “Tonight” had never occurred to

them at that point. They just had time to fill at the 11:30 point after

the nightly news and they were looking for somebody to do a show. The

one they hired was Hornsby. He was brought to New York to do some taping

and auditioning and so forth and he died two days after he reached New

York. It was a terribly sad story. He got spinal meningitis or one of

those things that kill very quickly.

What Pat Weaver did put on, not long after Creesh died, was “Broadway

Open House.” It was on for about a year or so. The chief emcee was

a comedian , nightclub comedian named Jerry Lester who was on three nights

a week. Two nights a week another comedian named Morey Amsterdam did it.

It had nothing to do with “The Tonight Show.” It was not a

talk show in any sense. It was sort of a loose variety show. They’d

have somebody sing a song. There was a tap dancer on the show who would

do a tap dance number. And Lester would do some kind of a sketch and one

way or another they would fill up the hour every night.

So in the meantime, this part of the drama overlaps my being brought to

New York and being hired after I left CBS by a fellow named Ted Cott,

who was the manager of the NBC station, WNBT, i think it was called then,

in New York. He had become a fan of my work. So he called over and said,

“I have a program I’d like you to do from 11 to 12 if you're

interested.” Of course I was.

For the first 14 months, the show was just seen in the New York, New Jersey,

Connecticut area because it was carried only on that one station. I had

no idea at the time Pat Weaver was again hoping to get a show for the

full network that he could offer to all of his stations. It occurred to

him in time that he already had such a show on his NBC station in New

York. The show was enormously successful. There was no competition. Nobody

else was doing anything like it. Most stations were showing old Charlie

Chan movies or old Hopalong Cassidy films. Because we had no competition

and we were doing a very good show, there was an enormous popularity.

Those things, I think, could only happen in the early days of television.

He called and said, “Would you like to do your show on the network?”

So at that point they simply changed the name of the show from “The

Steve Allen Show” to “Tonight.” The reason he wanted

to use that name was he had “The Today Show,” which was already

successful in the morning with Dave Garroway as the host of it. It was

not a comedy show. It was pretty much what it still is: news and weather

and that sort of thing, interviews. So that's how “The Tonight Show”

got started.

Q: So many people got their breaks on the show. I was

wondering how you found all the people. Did you have someone scouting

the country for talented people?

A: No, there were so many talented people in New York

alone we didn't have to do any scouting. Since then I've occasionally

found talented people here, there and everywhere. A show attracts people

who want to be on it. It's that simple. So we didn't ever have to call

up any agents and say who have you got? It all happened by individual

happenstance.

There was a late night — I don't know what to call it — it

was sort of a rotten show. It was on the ABC station in New York. Its

host was a disc jockey who had no talent although he was a nice fellow.

But that was part of the problem. He would just say good evening and make

small talk. There, however, was one exception. There was one marvelous

element to the program. There was a funny guy. His name was Louis Nye.

I'd occasionally watch this late show. It was really groaning time as

far as entertainment was concerned, except for this one guy who was always

funny. So about that time I was starting my local version. I just happened

to run into him in the lobby of the NBC, the RCA building there in New

York. I said, “Oh, you're Louis Nye.” He said, “Yep.”

He didn't know who I was. I said, “I'm going to be starting a new

show soon. If you're available I'd like to book you for some shots.”

So that's how he joined us as one of the early members of our company

on “The Tonight Show,” the local version of it.

There was this young singer, he was 17 years old at the time, Steve Lawrence,

he auditioned. He was a good singer and we were looking to staff the show

with regular singers. So he was our first member in the musical area.

And then a few weeks after that I met at a record company in New York

a young woman named Edie Gorme. They had never known each other before

that time but they met on the show and eventually married, as you know.

The third addition was Andy Williams. We also had a good young singer

named Pat Kirby. Things all fell into place one at a time.

And then because that show was so successful, NBC asked me to do a much

more important program because it was in prime time. America still goes

to bed at 11 o'clock. So most Americans only see “The Tonight Show”

or shows like it on Friday night. The reason is they have to get up. But

when you're on at 8 o'clock on Sunday night, everybody sees you. So I

did that for the next few years and for a while I did both shows, but

I eventually realized I had bitten off a little more than I can chew.

“The Tonight Show” I could have done, if they sent the cameras

to my house, in my pajamas since it's really one of the easiest jobs in

the history of labor. But the same is not true of heading up a primetime

big deal comedy show. That takes talent and a large staff of people.

Q: Did the network interfere much with either show?

A: The only show they interfered with, although they

quickly withdrew with some embarrassment, was if you could believe it,

the late-night show, “The Tonight Show.” Now they had selected

it in the first place because it was already a smash success. There's

the old saying if ain't broke, don't fix it. Nevertheless, they began

to monkey around with a hit. They came up with a number of suggestions.

As a rationalist, I've always listened to advice and suggestions and criticism

from everybody. And I think it's very smart to do so because vice presidents

and presidents and CEOs can make some really dumb suggestions and the

parking boys and the ushers will occasionally give you a good suggestion.

So you shouldn't be prejudiced or against an idea because of its source.

You should listen to it, and I did. But all the suggestions — there

were only three or four of them — the NBC programmers were giving

us were really dumb. In fact, at first we thought they were kidding.

To give you a specific example, here we were doing this swinging talk

show. One of the network suggestions was that they would take our announcer,

Gene Rayburn, who was just a straight announcer, lovely fellow but just

an announcer. So their idea was to interrupt all the wonderful music and

all the wonderful comedy and all the wonderful interviews and all that

and have Gene do a weather report right in the middle of the show. With

emphasis, and this is the really cuckoo part, on ski conditions. It seems

like he did it for about 10 days and the nuts and bolts were very primitive.

They gave him a blackboard and some chalk and he would hit the chalk several

times. That would represent snow. He was embarrassed himself. He didn't

want to do it. He realized it was a dumb idea.

I remember sending a memo to all the fellows. I said, “Gentlemen,

I hope you have done some research determining what percentage of the

American people care about skiing. My own assumption is it's a very tiny

percentage, and even among that tiny segment of the American population

what percentage might be contemplating going to a ski resort within a

given time frame.” Poor Gene got stuck with this embarrassing snow

condition report and then after about a week or so they dropped it with

no further comment.

Another idea wasn't as dumb as that one was, but it just was impractical,

given that ours was a swinging jazz party and comedy show, a happy time

every night. They thought that since we were half a block from Broadway,

it would be marvelous idea to have a resident drama critic who would come

on the show every night and tell us about the excitement that had just

transpired earlier that evening on the Great White Way. Abstractly, this

is not a dumb idea, it was just terribly wrong. The gentleman chosen for

the job, a social friend of ours named Robert Joseph, was not a very fascinating

speaker so it was four minutes of dullness as he would give his reviews,

talking about mostly unknown actors, plays that were not any good anyway.

Q: It seemed that would drag the show down a bit.

A: Of course. The laughter would stop. The audience would

frown at us for a while as if to say let's get back to the fun. Did NBC

try to influence the content of the show? Yeah they did and negatively.

Fortunately they stopped. They didn't give us any suggestions at all about

the Sunday night show except a suggestion we already knew: to book as

many stars as possible because we were opposite what was even then an

institution, the CBS Sunday night 8'clock entry “The Ed Sullivan

Show.”

Q: Not every comedian likes to share the laughter, but

you had some of the best comics ever on with you. Louis Nye, Don Knox,

Bill Dana. Tom Poston.

A: Oh, absolutely. The late night version in Los Angeles

was strictly a one-man operation. When I did “The Tonight Show,”

I did a lot of it myself without any particular help, but as soon as the

decision was made to start the primetime show, I got a lot of advice from

people who meant well. They said, in effect, “The Tonight Show”

is already so marvelous I hope you're going to do that same great stuff

at 8 o’clock.

And to all of them I said, “Absolutely not.” I said “That

works only because people are half asleep in their pajamas.” I said

“That won't compete against the Sullivan show with 14 superstars.”

Every week he had major stars. Sullivan himself, to this day comedians

make fun of him because he had big trouble with his mouth. He mispronounced

words. He forgot what he was talking about. He knew very little about

show business. He was by trade a journalist and a successful columnist,

but he had the journalists' sense of what's news, what's hot this week.

So he would always book whoever just threw the winning pass at the Rose

Bowl Game, whoever had won the heavyweight fight two nights before, plus

whoever was very hot in show business. So he had a highly rated show.

Even on nights when the show was pretty dumb, he always had good ratings,

so it was a tough job to go into that. But it worked out OK.

Q: The man on the street routine you did with Don Knotts.

Was that scripted?

A: Oh, yes. “The Tonight Show” was, I guess

you could say, 95 percent ad-lib and 5 percent scripted and the figures

are just bout reversed for a primetime comedy show, whether it's Sid Caesar's

or Jackie Gleason's or anybody else. There occasionally would be ad-libbing

when things went wrong, when a camera was out of position or an actor

forgot his lines or something. You can't suddenly check out of show business

at those bad moments; you have to ad-lib. But the shows were scripted,

and we were never on the street when we did the man on the street routine.

Some people are confused bout that because some of the funniest routines

that ever happened in show business history did indeed happen on the street

outside the studio. We called those routines camera on the street. Sometimes

people get the two phrases mixed up. But the wonderfully funny routines

with Louis Nye and Don Knotts, Tom Poston and Bill Dana and all those

great guys, they were all scripted. Actually, while the idea was my own

to do the man on the street thing, I don't think I deserve any great credit

for creativity there because all I was doing as every newspaper reader

knows is making TV fun out of something that had been a journalistic staple

for about 200 years. No matter where you put the dipstick into the history

machine, there's always some pressing question of the moment: Does president

Washington really have teeth made out of wood? Editors from way back have

sent out a reporter or stenographer. They pose the question to people

chosen at random on a busy street corner or supermarket or parking lot

and they take photographs and then they run their comments on the editorial

page. I was just having fun with that, doing that equivalent on television.

Q: You mentioned the camera on the street. You were the

first I think to turn the camera away from yourself and find the humor

outside the studio.

A: Yes, outside the studio and very often in the audience.

Roy Firestone once referred to our shows as the most borrowed from in

the history of television comedy. he was making an accurate statement.

The list of other shows which took our stuff lock, stock and barrel and

ran with it was a pretty long list. One of the popular routines on the

original “Tonight Show” and then on my subsequent talk shows

involved shooting closeups of people in the audience but putting a framework

around them such as “The FBI’s 10 most wanted.” Sometimes

we would construe it as a soap opera and I would play the off-camera announcer

summing up the action for those of who of you who've missed the last few

days of our show and that routine was always half written and half ad-libbed.

It had to be partly ad-libbed because of what it was. For example, the

script would say, “Yesterday you'll remember roger Crowlman …”

and then we would take a closeup of someone in the audience. They were

wonderfully funny routines ,which we did for years, and then quite a few

years later one of the other talk show folks began to do the routine exactly

as was, without even a switch.

Q: Is it frustrating to have been so borrowed from? you

don't get much of the credit anymore.

A: Yes. It depends entirely on the age. Nine-year-old

people don't even know who I am, much less remember what I did. I'll give

you an example of that. First of all, it's always been true. Each generation

has its own interests, its own tastes, its own celebrities. When I was

a kid, I didn't give a damn about Rudolph Valentino or Frances X. Bushman.

They were silent film superstars at the time but I'd never seen then in

the movies so for me they were just names I'd heard. Whereas women would

faint if they ever saw them. So I understand perfectly if somebody doesn’t

know who Johnny Carson is now. Already some kids don't know that, which

to me sounds impossible but there are such children.

In fact, just a week ago a friend sent me a letter in which he said the

day before he had happened to have lunch with Irving Berlin's daughter.

He told me he had occasion to hire five bright young people to work in

this publishing house. He came in that afternoon and was explaining to

somebody I just got back from a very interesting lunch with the daughter

of Irving Berlin. One of the young guys said, “Who?” He had

never heard of Irving Berlin. And none of the five bright young New Yorkers

in the publishing business had ever heard of Irving Berlin. Nobody gets

away from that. People know who you are if you're on television. You don't

have to be any good. You simply have to be on television.

Q: But would you like to get the recognition or the credit

for having created so many things, like the Answer Man and the man on

the street.

A: Oh, I do get credit, but again that's in the minds

of 52-year-old people. They know all about that. They talk to me about

it every time I meet them in a gas station or in the airport. But on the

other hand 22-year-old people don’t' know about it and why should

they? They don't care about it any more than I cared about Rudolph Valentino.

Q: Out of "The Tonight Show”hosts that have

come after you, who do you think has done the best job?

A: I really can't say. It's a very easy job, as I mentioned.

Hosting a talk show is analogous — and I'm not just talking about

“The Tonight Show” now — to being a disc jockey on the

radio. Nobody ever in the days of radio's basic importance put an ad in

the broadcasting magazine that said “Wanted: disc jockey. Must be

talented.” That would have been the stupidest thing. Some of the

guys have been talented. The key question is a very simple one: what did

the gentleman do for a living before he sat down behind that talk show

desk. In the case of Jay Leno, he was doing very well as a standup comic.

In the case of Jack Parr and Johnny Carson and myself, we were comedians

before we ever got into the talk show business. It's pretty hard to do

a bad job hosting a talk show. Here's a more interesting fact. Some extremely

lavishly talented people have attempted the talk show formula and not

done well at it. Isn’t' that weird?

Q: Why do you think that is?

A: Well, first let me mention the names. When he's hot,

there's no comedian in the business that's any funnier than Jerry Lewis.

He's one of the giant comics of the last 50 years. He was not a good choice

for hosting a talk show. ABC gave him the duty for a while and it didn't

work. One of my dear friends, a man I've loved since I first saw him in

vaudeville with his family at the age of eight or nine, is Donald O'Connor.

He sings. He does comedy. He dances like a dream. He's a bundle of talent.

He was not a good talk show host. A third example — also staggeringly

talented — Sammy Davis Jr. He did about nine things. He did them

all well. A true giant. He was no good as a talk show host. Jackie Gleason

once tried it for one weekend and apologized for the dumb mistake. So

here we have five or six of the most talented people in history and they

didn't hack it. You are really just an announcer. You're a master of ceremonies.

Another example that could be relevant was Ed Sullivan, who was probably

the worst master of ceremonies in the history of ceremonies. The audience

loved him because he made so many mistakes. The comedians made fun of

him and he was very endearing. He was a nice fellow. We were personal

friends. But the word talent never came up, and yet he had a successful

show for many years because all you have to do is emcee a dinner or on

television is say, “Here's Milton Berle,” and then Milton

is a real pro. He will amuse the audience for as long as you want him

to. But you don't have to amuse the audience.

Q: If it's that easy, why give it up? You could have

been the one and only host of “The Tonight Show” all the years.

A: I was doing both “The Tonight Show” and

the more important Sunday night show. The greatest comedy shows in history

were those of Sid Caesar. That's just a matter of record. It's not only

my opinion. Our show, and I'm talking bout the whole company now, was

in the No. 2 position. The no. 3, in the opinion of most of the comedy

writers in the business, was the Gleason shows and then the Lucy shows

and some other great comedy shows.

You could never have done the Sid Caesar show without the little factor

called Sid Caesar. So in the case of any comedy show that's successful,

first of all, for everybody involved it's a weeklong project. You work

like a dog for six days. You rehearse. You're constantly working. You're

getting very little sleep. You're doing something incredible. You are

producing a show that in many cases that is better than Broadway musical

comedy reviews that have been rehearsing for two years that still might

close by Tuesday night, and you're doing it in six days. Let's hear a

big flourish of the trumpets for all of the people who have been able

to do that. That requires full time concentration and consequently since

that was my assignment for the next several years I couldn't continue

with “The Tonight Show.”

Q: And you were making movies as well.

A: That's a relevant point. I made “The Benny Goodman

Story,” which required eight weeks of shooting, filming, and I was

hosting “The Tonight Show” at the same time and never missed

a night. As I look back, how I could do that? I guess I was just young

and ambitions and having that much fun. Show business for me has always

been fun. I read about other people having nervous breakdowns and God

knows what, but for me it was always to this day a delight. I'm

constantly performing all over the country. Every time on stage you're

having a party, at least I am.

Q: I have to ask you about Elvis singing to the hound

dog. Very famous segment. What was the reasoning behind that?

A: That was my own idea. And Elvis loved it. About 15

years after the event, some people who were not around at the time I guess

began to posit a totally preposterous theory that Elvis resented it, that

it was an insult to his dignity. Of all the stupid points I've ever heard,

that is the most stupid. How can it be undignified to have a man suddenly

dress like Fred Astaire. We put him in white tie and tails. He looked

handsome because he was a good-looking fellow. And he had the time of

his life. We hung out for the whole week he was on the show. We put him

in another comedy sketch that I wrote, a crazy cowboy type routine with

Imogene Coco and Andy Griffith, two giant stars in the history of television

comedy. He had a wonderful time. Nevertheless, the idea of having him

sing hound dog was my own.

It was the humor of incongruity. First of all, Elvis was taking a lot

of criticism for the hip swing. That never meant a damn to me. I had no

problem about that. He was a cute performer and he deserved his great

success, but as a kind of going to the other extreme, we presented him

in the most dignified circumstance possible with classical Greek pillars

as the set behind him and beautiful lighting and beautiful photography

and again in white tie and tails, which is the greatest look any male

person can have. He sang the song. We didn't touch the song. That was

his own thing. We didn't have any interest in how he should do the song.

We didn't tell him to do it as a minuet or an operatic thing, which would

have been stupid.

|

Wayne

Hicks'

Standup Comedy Blog

Please consider a donation

so we can continue this work!

Amazon Prime - unlimited streaming

of your fave TV shows and movies!

Get your FREE 30 Day Trial!

PR4 & PR5 Pages for Advertising

Everything you're

looking for is here:

|