you're looking

for is right here:

Save money!

| |

|

Everything

you're looking for is right here: Save money! |

|

|

|

|

PART THREE

/ Click here for part one

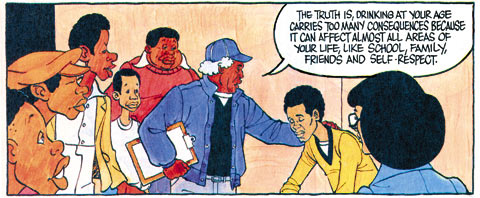

THE RACIAL ASPECTS Surprisingly, no serious attempt was made to cash in on the popularity of "Fat Albert." A short-lived series of comic books was published. A few stories were turned into books. "Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids" turned up on a lunch box, as fast-food giveaway toys and a board game. Cosby published two books of homilies, "The Wit and Wisdom of Fat Albert" in 1973 and "Fat Albert's Survival Kit" two years later. He also allowed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to use his characters for a comic book preaching the dangers of alcohol. Having so few products for sale stood in stark contrast to the merchandising pushes that were made for other shows of the day, for a clear reason, Scheimer said. He said companies didn't want to license the images of these black children - "Not because there's prejudice; because they thought nobody would buy them." "Fat Albert" wasn't specifically about being black - none of Cosby's shows before or since has been - but race wasn't overlooked. The characters, minor and major, were all black. But the program wasn't written for black children. It was written to reach everyone.

If anything, DiTillio said, he viewed the Cosby kids as older versions of the Little Rascals. "They kind of worked the way the Little Rascals used to work, getting into trouble. They always had a scheme." That didn't keep Cosby from playing up the racial aspect of the show in his doctoral thesis, for which he received his Ph.D. in 1976. "No other show previously on television has concerned itself so much with identifying with black children," Cosby wrote. "For the first time black children have the opportunity to see themselves through the animated characters of Fat Albert." But a common theme to the program is that differences should be overlooked, whether the difference was of height, sex or race. Ironically, Cosby's messages sank in more with middle class and lower-income white children than they did with lower-income black children, according to a study CBS conducted in 1974. CBS trumpeted the success of "Fat Albert" in reaching children, taking out a full-page ad in The New York Times and calling the show "an extraordinary experiment in television education" "The way I see the show," Cosby said about the TV series before its premier, "it will be so casual in its teaching, the children will never know they're being taught." FOCUSING ON EDUCATION Key to the success of the educational component of "Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids" was the presence of Gordon Berry, a Ph.D. and professor of education at UCLA when Scheimer went looking for an educational consultant. "When I first met Lou Scheimer, they - Bill and Lou - they had the concept for Fat Albert," Berry said. "They had the idea. They had characters and they had a point of view. One of the first things I was asked to do was to pull together somewhat of a concept paper on how you would introduce the notion of what we were calling then 'pro social messages' into television." The idea of educating children through television had until then belonged to PBS, specifically "Sesame Street," which relied heavily on the input of educators to craft the appropriate message. Commercial television was content to entertain, with few exceptions, such as "Captain Kangaroo." Filmation's decision to bring Berry in proved groundbreaking. "Gordon was fantastic," said Robby London, who wrote for "Fat Albert." "The great thing about 'Fat Albert' is that television frequently has lots of layers of advisers, but rarely does it have layers where each layer is an improvement. But 'Fat Albert' was actually a case where that was so." "We did not always agree, but they certainly always wanted my input," said Berry. "Obviously there's always somewhat of a disconnect between a person who's an academic and creative folks. I don't mean that there's any disagreement, but, after all, creative people have a certain vision that academic people do not have." TALKING ABOUT SEX London turned to Berry when he wanted to write an episode about venereal disease, a topic usually ignored during Saturday morning TV. "That's pretty far out for a show targeted for 12-year-olds and under, because parents obviously don't want you talking about sex with kids that young and understandably so," London said. "You don't want to encourage kids that young to engage in sexual activities. It would be very inappropriate of television to do that." London and Berry came up with the idea of implying "a connection between a disease and romance, which we played in the form of a kiss. We had characters kissing." The message: "If you get a sore, go to the doctor. Not really link it with sex, but sort of subtly link it with sex," London said. "We took on more hard-hitting issues as the show progressed," Berry said. "The material was more hard-hitting and we moved away from being teased about wearing glasses to issues related to bigotry, issues related to protecting to your own body to issues related to social diseases. That's what happened. The issues became more sharply drawn as we moved on and the show became more successful." Writers on the show were advised to seek out Berry. "We would just start with themes," DiTillio said, "stuff like somebody's vandalizing the school or an absent-minded girl leaves the gang high and dry by forgetting to show up for a key role in a play. Then Gordon would go through them and say, 'Well, I think that theme is good. I think this theme is excellent.' Then we'd go from there." Berry was careful to avoid letting generalities creep into the scripts, DiTillio said, to keep characters from being labeled bad or good. "We tried to say the kids are the kids and this kid may be doing something bad but he's not per se a bad kid," DiTillio said. "Gordon would watch that very closely. Rudy tended to be a mischief-maker, so he'd tend in some scripts to become villainous and we didn't want that. So Gordon would watch out for things like that. He'd watch out for racial mixtures to make sure that we weren't saying that all the white kids are bad and all the black kids are good, or even the other way around." According to the story bible for the show, writers were urged to seek Berry's opinion. The bible also told writers they needed to be able to answer "yes" to two questions before they could begin writing: "1. Can the show provide a positive contribution to the problem we are considering? 2. Will this be an entertaining show? No film, however worthy its intent, however altruistic its makers, is fulfilling its primary obligation if it does not entertain!"

|

TV

on DVD

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||||||||||

Save money! |