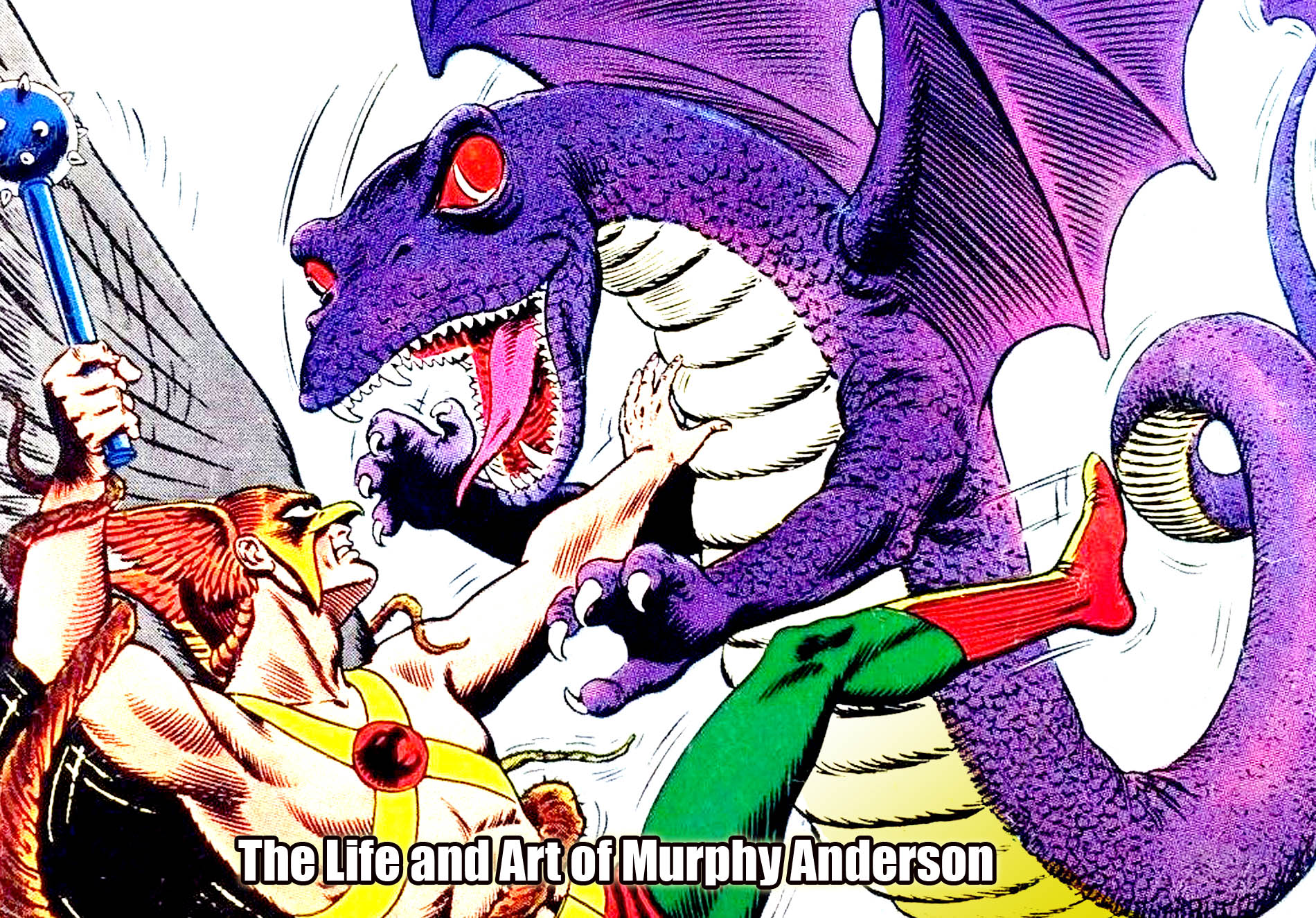

He also dropped dimes on crudely drawn 64 page four- color pulp mini-magazines, a curious new addition to the newsstand at the Southern Fruit Store on Market and Elm, including the rst appearance of Superman in Action Comics and Batman in Detective, two characters and titles he would one day become closely associated with. For fun he wrote and drew his own home-made comics, winning an art contest sponsored by the Greensboro Daily Record when he was 14. Amy Hitchcock was a classmate, “At Central Junior High there were two boys that sat together all the time, sort of separate from everybody else, and they drew in their notebooks all the time. One of them always drew cars but Murphy, we called him M.C., he always drew gures. My impression of him was that he was withdrawn, quiet, and always did his own thing, but he was pleasant.” Later, Murphy and Irwin Smallwood became co-editors of Greensboro (now Grimsley) Senior High School’s newspaper.

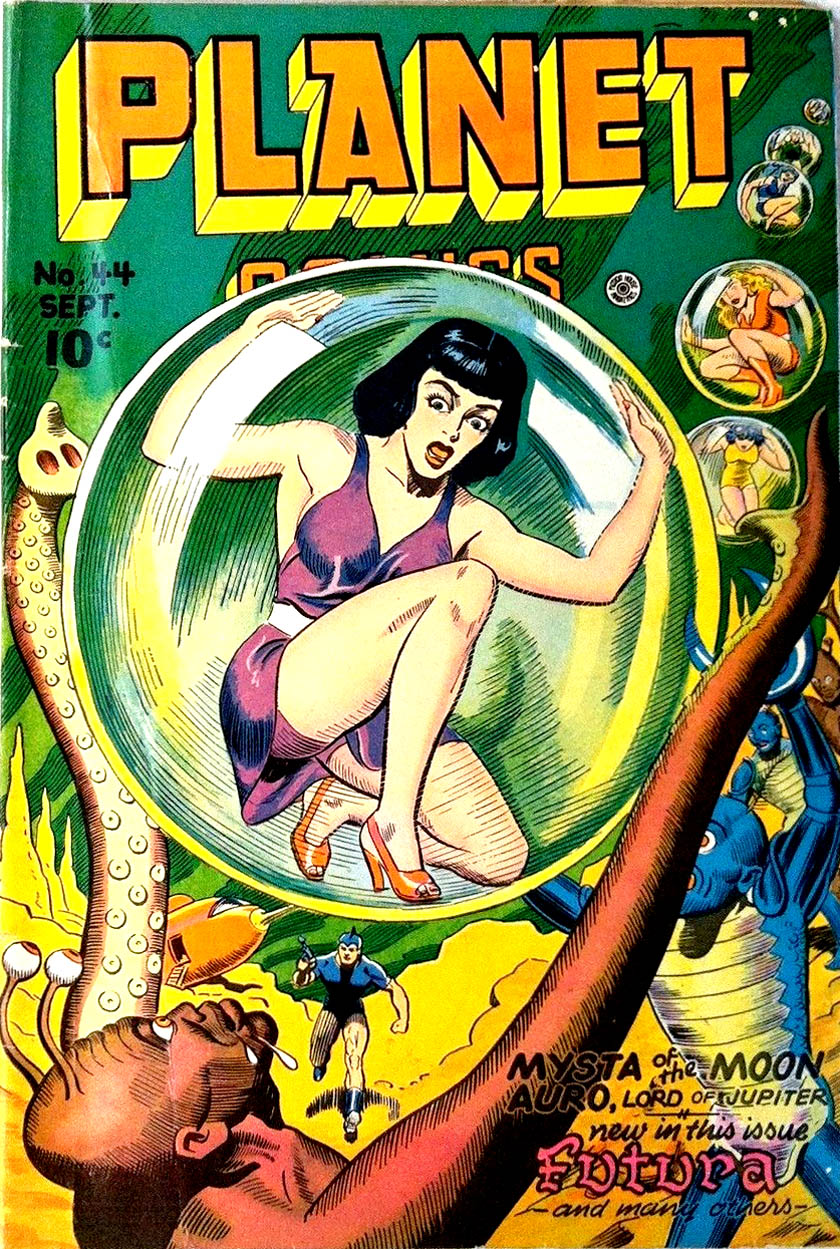

After content bundler Harry “A” Chesler rolled his grapes over Anderson’s portfolio—heavily in enced by Lou Fine and Will Eisner who were known for their realistic, anatomically correct gures, alluringly distressed damsels and spectacular space age machinery—he referred the teenager to Fiction House on the corner of 53rd Street and Fifth Avenue, home of Planet Comics who’s main selling point seemed to be the undulating breasts belonging to whichever curvaceous blond was being snatched up by salivating BEMs that month. Mars needs women! The Fiction House bullpen worked in what we now call Marvel-style, with artists blocking out the stories from a loose premise; dialogue was added afterward. As Murphy Anderson related to biographer R.C. Harvey about the artists he shared a room with, “Everyone was talking about Alex Raymond and Flash Gordon. Most of the work at Planet Comics was in uenced or copied from Raymond, sometimes from Milton Caniff or [Hal] Foster.”

His enthusiasm for the character and interstellar efforts for Planet Comics helped seal the deal. After a nearly year-long tutorage under Buck Rogers’ overseer John F. Dille, who admittedly “wanted the cheapest artist he could find,” Murphy took over the daily art chores in December of 1947. “I grew up on Buck and it was a dream come true when I worked on the feature.” Not particularly happy in the long term, creatively or financially, Murphy left Buck Rogers in 1949. No going back to Fiction House in New York, Planet Comics was in a tailspin, so Murphy and his bride instead made their way to Greens- boro where, during the day, he served as of ce manager for his father’s edgling business, the Blue Bird Cab Company (“Dial 5112: Then Count The Minutes”). At night he applied brush to paper for Ziff-Davis magazines before agreeing to join their ill-fated comic book line in New York under the direction of Jerry Siegel, one of the creators of Superman. Before long, Murphy found himself once again canvasing the concrete jungle, portfolio in hand.

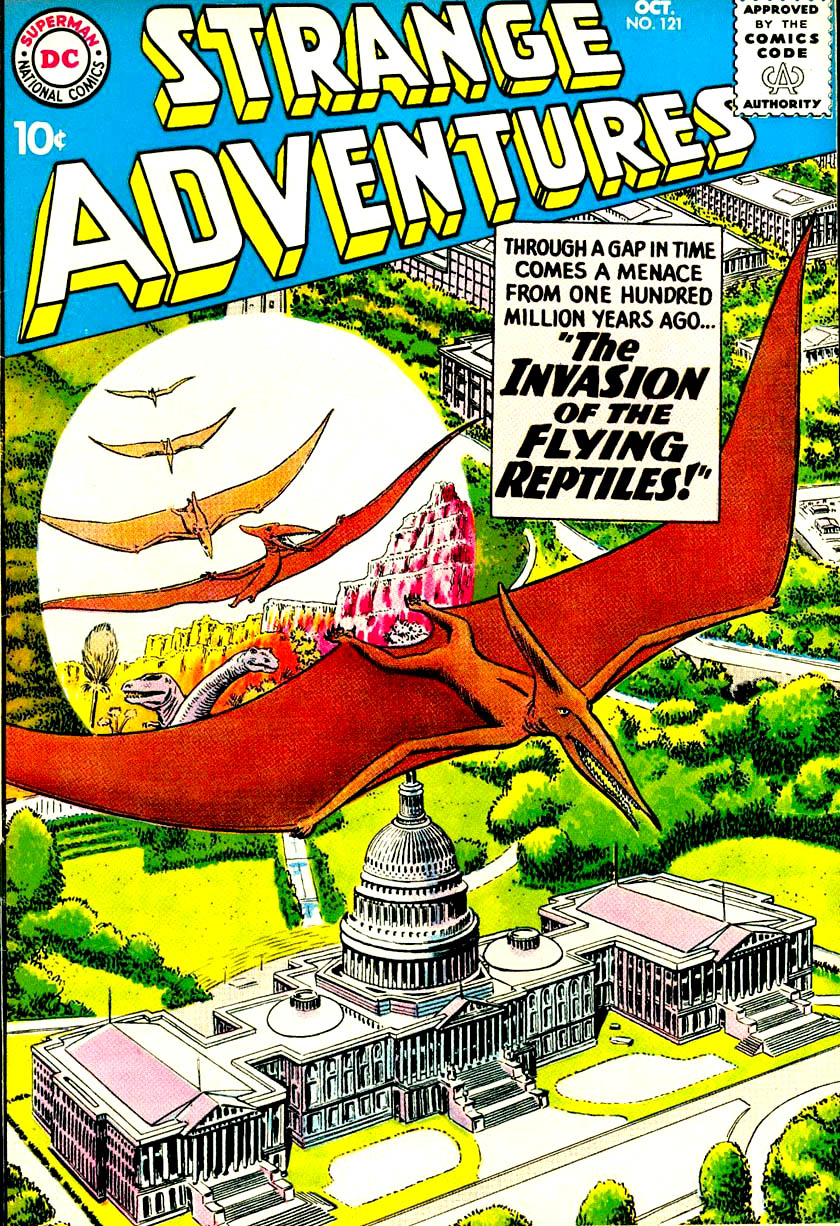

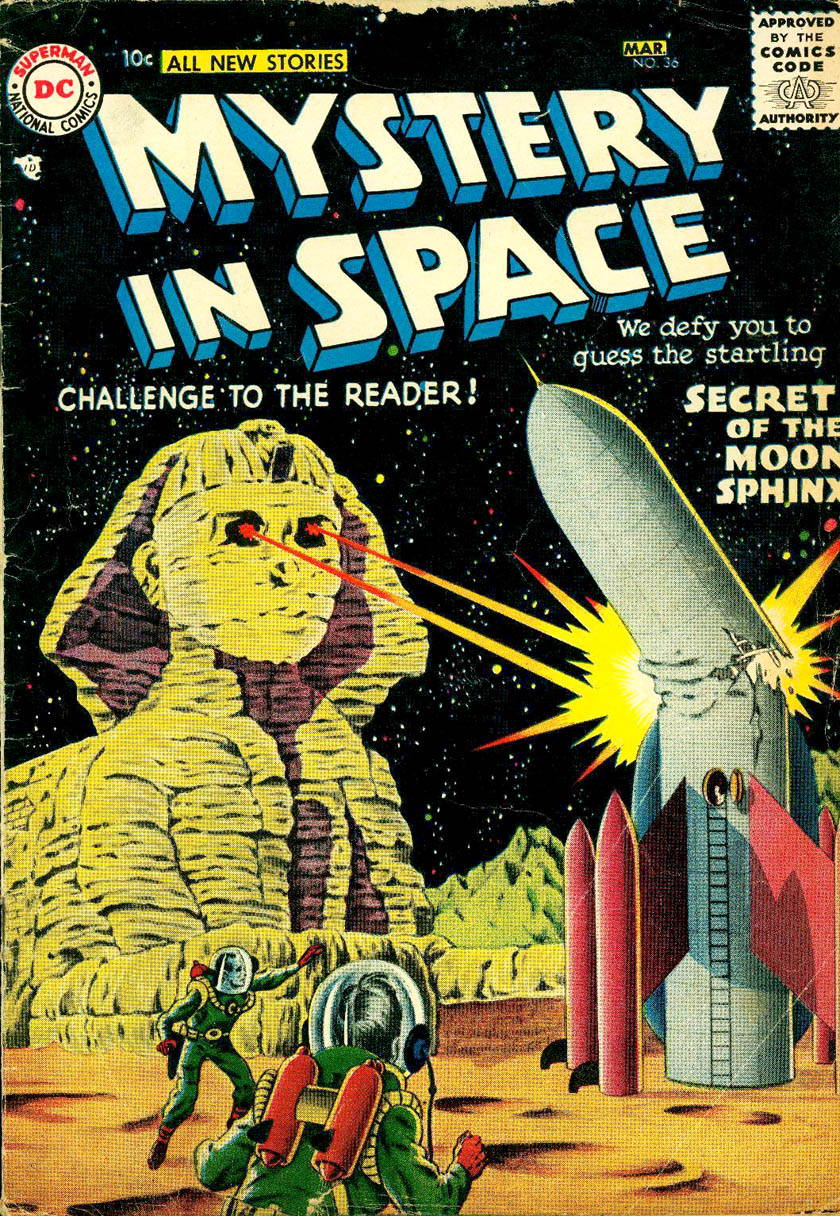

With the raising children to consider, Murphy wasn’t ready to give up on his Carolina roots. Proving himself a reliable player over a two year period, Schwartz allowed Murphy to mail in his pages from Greensboro, Back home trafficking for Blue Bird Cab, Murphy spent nights illustrating the adventures of Captain Comet and dreaming up compelling covers populated with pointy-eared giants capturing fighter jets in butter y nets, invading radioscopic weirdos from other dimensions terrifying the tourists, genetically superior gorillas confounding the laws of man and nature, scaly-skinned martians broadcasting the end of human civilization. Stories were then written around these phantasmagorical scenarios.

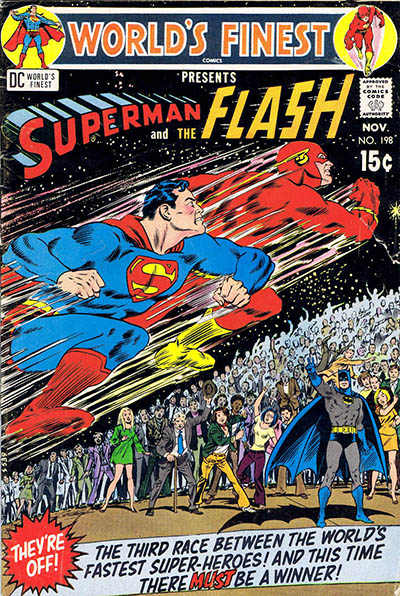

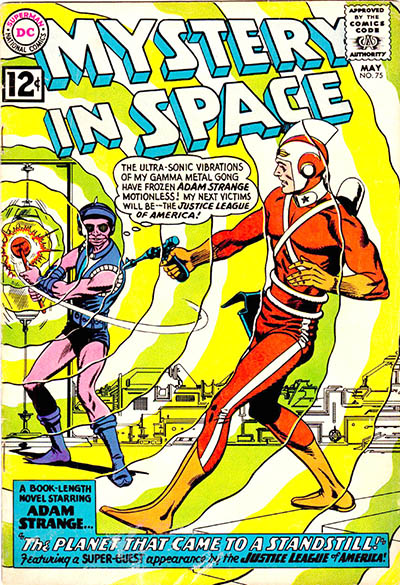

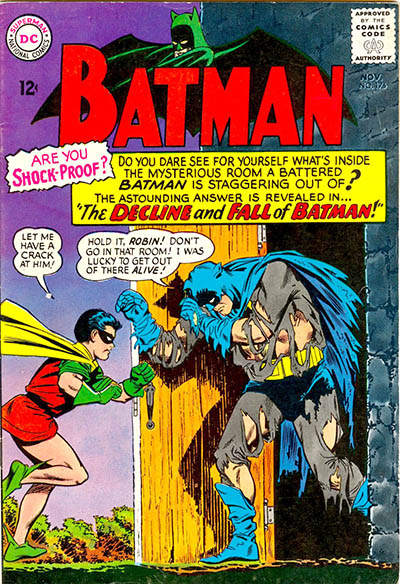

Along with writer John Broome, Murphy originated The Atomic Knights in 1961. Although infinitely more fanciful (for instance, the Knights are waited on by anthropomorphic plants) this feature has a lot in He also created the sexy sorceress Zatanna and, with few exceptions, drew and/or inked the rst 7 years of covers for Justice League of America. It was he that Julie Schwartz turned to when reviving Golden Age back-of-the-book heroes like Dr. Fate, Hourman, and The Spectre. After Hawkman was given

Comic strip artists, as opposed to their comic book counterparts, were very well regarded in society as purveyors of wholesome family entertainment. When folks picked up their morning or afternoon newspaper most turned first to the comics page. As such, Murphy Anderson commanded more respect as Buck Rogers’ delineator than he could ever hope to have laboring over DC’s juvenilia. Still, Murphy chose pop culture’s red-headed stepchild over Buck Rogers after just two turns around the sun. This meant mostly inking other’s pencils at DC, most notably Carmine Infantino (Adam Strange, Batman) and Gil Kane (The Atom, Green Lantern). Infantino benefitted most notably, other inkers were too severely covering over his line work or exaggerating his worst traits.

|

Comic Book Artist

Dateline NBC : The Brutal Murder of |

Get it here! SAVE MONEY |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Everything

you're looking for is right here: Save money! |

A college dropout facing certain military service in 1944, Murphy borrowed $100 from his skeptical father to make the rounds of New York City’s funny book publishers. Whether he knew it or not Murphy was marching into what has become known as the Golden Age of Comics, so christened because sales were so astronomical, upwards of 6 million copies per unit, that publishers were setting up shop in every corner of The City. Their biggest problem was securing enough newsprint to meet demand.

A college dropout facing certain military service in 1944, Murphy borrowed $100 from his skeptical father to make the rounds of New York City’s funny book publishers. Whether he knew it or not Murphy was marching into what has become known as the Golden Age of Comics, so christened because sales were so astronomical, upwards of 6 million copies per unit, that publishers were setting up shop in every corner of The City. Their biggest problem was securing enough newsprint to meet demand.  Anderson continued slinging ink for Fiction House even while serving two years in the Navy as a radar repairman stationed in Chicago; that’s where he met his soon to be wife Helen. In 1946, after his stint in the military was over, Murphy was scouring the hind pages of the Chicago Tribune when he happened upon a notice from the National Newspaper Service in search of an artist for an “adventure comic strip.” That strip turned out to be Buck Rogers.

Anderson continued slinging ink for Fiction House even while serving two years in the Navy as a radar repairman stationed in Chicago; that’s where he met his soon to be wife Helen. In 1946, after his stint in the military was over, Murphy was scouring the hind pages of the Chicago Tribune when he happened upon a notice from the National Newspaper Service in search of an artist for an “adventure comic strip.” That strip turned out to be Buck Rogers.  Julius Schwartz, editor for National Periodical Publications’ (as DC Comics was known in 1951) new line of science ction comics, immediately recognized Anderson’s work as compositionally superior to—and more nicely rendered than—many of the company’s artists, most of whom had little affinity for sci-fi. Murphy walked out after that meeting with a script to illustrate.

Julius Schwartz, editor for National Periodical Publications’ (as DC Comics was known in 1951) new line of science ction comics, immediately recognized Anderson’s work as compositionally superior to—and more nicely rendered than—many of the company’s artists, most of whom had little affinity for sci-fi. Murphy walked out after that meeting with a script to illustrate.  He and Helen relocated to the New York metropolitan area in 1960 in order to work full-time for DC, a company undergoing an unexpected resurgence. Editor

He and Helen relocated to the New York metropolitan area in 1960 in order to work full-time for DC, a company undergoing an unexpected resurgence. Editor After the Soviet launch of Sputnik spread space fever across the USA, Murphy was summoned to again reinvigorate Buck Rogers in 1958. This time he was enlisted for both the dailies and Sunday full page. Murphy’s more modern, slick, detailed artwork was light years ahead of the antiquated approach that preceded him.

After the Soviet launch of Sputnik spread space fever across the USA, Murphy was summoned to again reinvigorate Buck Rogers in 1958. This time he was enlisted for both the dailies and Sunday full page. Murphy’s more modern, slick, detailed artwork was light years ahead of the antiquated approach that preceded him.  Anderson infused Infantino’s uid pencils with a majestic quality, a pitch-perfectness neither was able to fully achieve without the other. (Gil Kane was equally well-served by Anderson but Kane traveled to higher artistic planes with a number of other outstanding collaborators, among them Wally Wood, Nick Cardy and especially John Romita on Spiderman in the seventies.)

Anderson infused Infantino’s uid pencils with a majestic quality, a pitch-perfectness neither was able to fully achieve without the other. (Gil Kane was equally well-served by Anderson but Kane traveled to higher artistic planes with a number of other outstanding collaborators, among them Wally Wood, Nick Cardy and especially John Romita on Spiderman in the seventies.)