|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| |

|||||||

by L. WAYNE HICKS

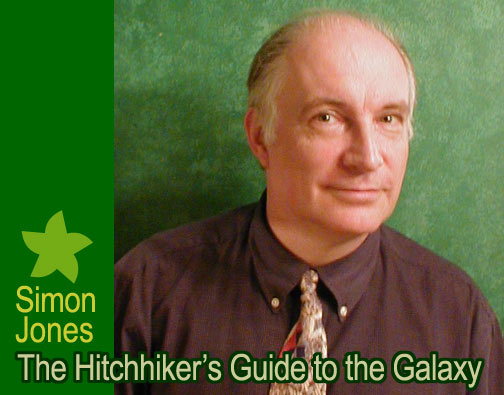

First Jones' voice and then his face became legendary in Douglas Adams' hugely popular story, which began as a BBC radio drama in 1978. Adapted first for print and then for a BBC television series that found a home in America on PBS, "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" is the story of Arthur Dent (played by Jones), the last Earthman left after his planet was destroyed.

Decades after the BBC first broadcast the radio series, Jones and the surviving cast returned to the studio last year to record a dramatized version of the subsequent books in the five-book series, including "Life, the Universe and Everything" and "So Long and Thanks for all the Fish." Timed to coincide with the release of the movie, the BBC will begin airing the "Fish" episodes in May and the television arm will rebroadcast the six episodes that comprised the original TV program.

During an interview, Jones reflected on the various incarnations of "Hitchhiker's Guide," the life and times of Douglas Adams and his pursuit of a good cup of tea. Q: What's your role in the new movie? The press kit identifies you as a "ghostly figure." Can you offer any more details? A: My, my, I even have a name? I am on for about 30 seconds as the Magrathean answering machine, though I am in 3-D. The only bit of 3-D, apparently. I can't believe they'll give out glasses for 30 seconds. Q: When did you first meet Douglas Adams? Was it in college? A: Yeah. Yeah. He had always wanted to join the Footlights Review Club. The only way to join it was indeed to come and perform your own material, or at least somebody else's. That's how you got in. Q: You were already a member? A: I was already a member. I was in fact chairman of this particular one that he came on to audition for. We did smokers, as they were called. They were twice a term. Or at least once a term, anyway. Semester. And people would come along. I had a really grim morning. Various people would come along doing frightfully intellectual sketches, none of which would raise a titter from me. Douglas came on with two friends, proceeded to drain a glass of water and then while one of his friends cranked his arm he spat the contents into the face of the other. It was a sort of human water pump. Actually struck me as inordinately funny. The rest of the committee thought it was extremely silly and there wasn't any point in it at all. But I had my way. I said, "Of course he must join, this man is clearly a genius." No, I say that now. I said, "He's made me laugh. He's the only who has. For goodness sake, isn't this about making people laugh?" I overcame their opposition because after all I had the swaying vote and he got in and apparently he remembered that. Word got back to him that I had stood for him. Q: Did he stay with Footlights for very long? A: Yes, he did, while he was at Cambridge. Q: Did his humor following similar physical form? Or was he doing more literary humor? A: I think that was his least sophisticated piece, I suppose. I don't remember whether there was any dialogue. I doubt it, somehow. I don't actually remember whether he did any other material, either. All I remember is that particular piece. But clearly why he wanted to join Footlights is he wanted to follow in the footsteps of the Beyond the Fringe people and the Monty Pythons, some of whom had passed through it, those who hadn't been to Oxford instead. And he was clearly very influenced by the Pythons, as far as he went on to work with Graham Chapman. We did the pilot of a television program called Out of the Trees, which was a bit derivative of Python.

Q: That was the first time you worked together outside of Cambridge? A: Yes, I think it was. I remember it was about five years later, I think, he called me up and said, "I've written this program, a science fiction show and the BBC's finally agreed to do it. I've been nagging them for a long time. And I'd like you to play the survivor of Earth. You're the only one I think could do it." Which was very nice. Of course, I said yes, thinking he'd written the part with me in mind. I have done ever since, until more recently when I've come to realize perhaps he was Arthur Dent rather, more than I. Q: Why do you think he was Arthur Dent? A: Many characteristics, I realize now, that he seemed to have. That both of us were always going on about not being able to get a decent cup of tea. It just cropped up, actually, in the aftermath of his death when people were talking about him. I began to think that he sounds more like Arthur than I do. He probably was. Q: What did Douglas like best about the process of writing Hitchhiker's Guide? Was it having finished it? Was it just having the ideas? A: I think having finished it was an enormous relief to him. Sometimes he had the ideas and sometimes they took a while to come. I do remember when we were recording the first series and he had no idea how it was going to end. It was only by dint of the fact that we were in the recording studio and had nothing to say and the story is coming to an end and this is it that he actually got to the end of it. Q: Was there any kind of sense of desperation at that point, that maybe it was going to stop and not end? A: No, actually. We knew it was going to end somehow. He was passing these sheets out to us with bits of script written on them. We knew they'd put it all together in the sound booth later. That was always something of a mystery of recording Hitchhiker's Guide anyway because we did it all in bits. We had no live audience. We hardly ever met Peter Jones, who played the voice of the book, because he came in later, in his own soundproof booth. Sometimes we forgot out people who were in the soundproof booth. The man who played Marvin the robot, I think he'd been in there an hour or so and finally he said can I come out now? They'd completely forgotten he was in there. We only had a day to record each episode. Basically only Douglas or Geoffrey Perkins knew precisely what was going on in the story. Q: Perkins was the producer? A: Yeah. Q: That was the first incarnation of Hitchhiker's Guide. A: The radio version, yes. Q: Did you have any idea it would become this worldwide phenomenon? A: Not really because the BBC had, first of all, been very reluctant to put it on because there hadn't been, they said, since Journey Into Space, any science fiction on the radio. It seems hard to believe now because it's so obviously the right medium for it. Then they said, I can only repeat what they said, but now they say of course it was the way they create a cult, it was intentional marketing. So confident were they in this particular program that they put it out at 10:30 at night on a Tuesday evening. To me that sounds like the next thing to putting the cat out, really. And it was indeed when people were putting the cat out or making their goodnight cocoa or whatever it was. People did get to hear it. And for the first time in the history of the BBC there was such a clamor for people to hear the episodes they missed - because it doesn't make much sense if you're coming halfway through - they were forced to repeat it immediately. Of course they say that was entirely in the plan, now. But if they'd been that clever, they also would have secured the rights to the books, which they did not because they didn't think they would sell many. They only sold 15 million, I think, worldwide.

Q: You didn't get to read the radio script from beginning to end. You mentioned it wasn't finished. But you agreed to do it based on what he said or what you read up to that point? A: I hadn't read anything. I said why not? He was a struggling writer. I was a struggling actor. It seemed like the sensible thing to do. No, no, I wouldn't insist on reading the script. Q: When did you realize Hitchhiker's Guide was a success? A: I think it was at the end of the broadcasting of the show when we suddenly began to get this feedback. Because pressure suddenly came on Douglas quite obviously to write the books, the first two anyway, which were fairly straightforward and I think he approached them with a certain amount of ease because he had already written the scripts so there was only the question of novelizing them. Of course he couldn't leave that alone so the plot is therefore different. Q: That's the surprising thing about the various incarnations. A: Yes, it is. Q: The story does change. A: I think he got easily bored. Q: Do you have a favorite version of the story? A: I think the radio. Q: Why the radio version? A: The scenery's better. It's as simple as that. The TV series is very firmly grounded in its period. If you look at it now, it's almost embarrassing. That was the BBC at the peak of its special effects, at that time. They spent vast quantities of their budget on this particular project. And yet the very first thing I heard when I came over to America was from an interviewer who said, "What I really liked was the deliberate tacky nature of the effects." And I said, "Yes, yes, absolutely. Well it was intentional, of course." Realizing that of course we were post-Star Wars and it did look cheesy. In a way that's part of its charm now. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TV Shows on DVD/ / / / / / / Classic TV/ / / / / / / Punk Book/ /

/ /

/ / / / / / /

Holiday

Specials on DVD / /

/ / / / Classic

Commercials |

|||||||

Save money! |